Paid Subscriptions today are half price!!! Take advantage to see “Grand Narrative” in full.

CONTENTS:

PROLOGUE: The Oxford Union has betrayed British Values

INTRODUCTION: Who’s afraid of grand narrative?

BOOK 1: LANGUAGE: ON LIES & CIVILIZATIONAL DEMISE

1.1: Living a Lie

1.2: Corruption of the Masses

1.3: The Dangerous Confusion of Language

1.4: The Great Genocide Lie

1.5: Hands off Churchill!

1.6: In Praise of the British Empire for Abolishing Slavery Worldwide

1.7: Declaring War on Post-Modernism

1.7.1: Part 1: With “Authentic Feeling”

1.7.2: Part 2: A Genealogy of "Woke" Linguistics

1.8: Justice Lost

1.9: The Problem with Atheism

1.10: Word Inflation

1.11: Thou Shalt Not Lie: On the Destruction of Worlds

1.12: Freedom of speech?

1.13: Democracy cannot survive in a world that accepts lies as truth

1.14: The Silent Image

BOOK 2: TRUTH: ON THE BIRTH OF HUMAN AGENCY

BOOK 3: SOVEREIGNTY: ON THE DEMOCRATIC NATION

BOOK 4: NARRATIVE: ON THE FULFILMENT OF MEANING

BOOK 5: FREEDOM: ON WRITING THE NEXT CHAPTER

BOOK 6: COVENANT: ON CREATING A NATION OF NARRATIVE

BOOK 7: NATIONHOOD: ON EXPANDING THE NARRATIVE

BOOK 8: LEADERSHIP: ON REACHING THE PROMISED LAND

BOOK 9: PEACE: THE END OF THE JOURNEY

Declaring War on Postmodernism [Part 2: With reason] - Chapter 1.9.2

The linguistic roots of “woke” ideology

“There are two different kinds of people in the world….”

“There are two different kinds of people in the world….”

How many times have we heard this phrase? The insistent idea that the complex mass of humanity can be neatly divided into two categories. But those who resist the clarion call with passionate refusal are soon dragged into its irresistible orbit. For though we rail against simplicity; though we anger at dividing the world into us and them; we soon succumb to its temptation:

“There are two different kinds of people in the world, those who use phrases of the type ‘There are two different kinds of people in the world….’ and those who avoid such distinctions”. Oh dear…

Dichotomous thinking is at the heart of language and from its grip there is no escape. In every encounter with the world, we are forced to make distinctions. From the most mundane to the most complex of ideas we divide the world into x and not-x. At the most humdrum of levels, we classify whether everyday objects make the categorical grade. Is this a table or is it not a table? If it has 4 legs, is of a certain height, is of a certain shape and has a particular function, it’s a table. In most cases, the appropriate definition is clear. But as with the law, there are hard cases. Is it a table or a workbench or a movable breakfast bar? Here we either concede that it’s a table, choose an alternative, pre-existing category or in extremis, invent an entirely new denotation. Our world is mediated through either-or categories into which we unceremoniously ramhorn all that we encounter1.

The Law and the Facts

But the linguistic magnetism towards division is most starkly brought to life in more abstract domains. Their Lordships in the appellate courts are tasked with defining the limits of the law; does this or that action fall within the ambit of the legislative clause?2 Let us examine a classic example: Theft. In most cases, whether an act should be categorized as such is clear. The only question before the jury is “Did they do it?”. But upon appeal, controversy may remain. Even where the facts may be agreed upon, the law may not. Theft is defined as “Dishonestly (appropriating) property belonging to another with the intention of permanently depriving the other of it”3. In a challenging factual matrix, every non-function word in this sentence may be susceptible to legal challenge:

Do the facts amount to appropriation?

What is dishonesty?

Did it belong to another?

Did the thing taken amount to property?

Was there an intention to permanently deprive?

Dishonesty, property, appropriation, permanently deprive, intention and another: all these are linguistic concepts about which we are called to decide: are the facts to be categorised as x or not-x? Property as with tables is daily subject to dichotomous decision making. In Somerton v Stewart4, referenced in a previous chapter, Lord Mansfield was asked to decide upon the matter of property. Could an escaped slave be considered as property or belonging to another? According to our modern philosophy, and indeed according to the philosophy that has existed since time immemorial on the British island, the answers to these questions are clear: no person may be considered property nor as belonging to another. But in the era of the Atlantic Slave Trade such questions were controversial and the appellate court was called to rule defintively.

Today, where such questions are settled, others emerge to take their place; the matter of forced consent being of particular interest. But note this: even though language, by its nature, necessitates distinctions, language is separate from the underlining reality. Where the Supreme Court is called to decide upon the definition of appropriation, the case’s factual matrix has already been determined by the jury. Assuming that the 12 men and women have correctly determined the true sequence of events, they have, through so doing, determined a reality beyond the realm of legal definitions.

First the lower courts decide the facts. Then the appellate court categorises the facts in relation to legal concepts. Indeed the Common Law legal system is the most shining example of the distinction (!!) between lingustic distinctions and pre-existing facts. Put simply, there is truth. Jacques Derrida was wrong to say 'Il n'y a pas de hors-texte' (there is nothing beyond the text)5.

Reality and Defining Reality

Tornados exist in the realm of reality. They really do. The a posteriori decision to define the phenomenon as a tornado as opposed to a hurricane is a human construct within a particular community. But the thing being described by Great Plain Americans as a tornado is a real thing. Different cultures may define natural phenomena in different ways according to their linguistic understanding. Some may make no division between snow and rain, classifying both as mere precipitation. Other languages may contain 30 different concepts for 30 different types of rain, never referring to those 30 concepts together simply as “rain”. But rain really exists.

As for everyday matters, so with the abstract. Some cultures may have invented “hope” on the basis of seeing the benevolent hand of God in history. Others may - literally - have no hope6. In an era before mass trade, some cultures may have been shielded from the “Tivka”7 of the Hebrew Bible and thus never have made that distinction. Now, one may argue about whether hope or love are human constructs invented apart from reality or whether they are embedded within it. But either way, the events - the phenomena - causing Hebrew culture to categorise according to hope or not-hope were real events. Truth is true.

Given that real phenomena can be defined in various ways by different cultures, we can accept the legitimate existence of different perspectives. There is more than 1 right answer. Community A can look at a phenomenon and make a distinction x versus not x. Community B can look at the same phenomenon and make an entirely different y versus not-y distinction. Assuming the accuracy of both communities' observations, neither is more “right” than the other. Both are valid distinctions. But this is not relativism; for as with appellate courts, the factual matrix is agreed by both parties. A posteriori linguistic definitions do not affect the underlying, mutually agreed reality.

But though there may be more than one right answer, we may not conclude that all answers are equally valid. There are determinedly false responses. Indeed postmodernism is falsity defined. The Derrida postmodernism idea that 'Il n'y a pas de hors-texte', that there is nothing prior to linguistic distinctions, is wrong. Period. Phenomena are real. Science may help us understand those phenomena better, guiding us to see them closer to how they really are, eliminating our outdated superstitions, but phenomena are real. Language’s role is to make sense of those phenomena after the fact. The denial of truth, the idea that we cannot ask whether factual matrix A is x or not-x because even the factual matrix itself is a human distinction, cannot be maintained. When John entered the fruit shop and placed an unpaid for apple in his pocket, motivated by hunger, we can debate whether the facts amount to theft, but we may not deny the events of the day. The apple definitely went into his pocket “outside the text”; and the shop owner wants justice.

Postmodernists say that there is nothing below the surface; nothingness beyond the veil. Scientists claim that the “beneath” the objects that we intuit with our senses, there are atoms and molecules and cells which represent the true reality. But the postmodernist sees only human-imposed linguistic distinctions8. Kantians claim that behind the manifold cultural perspectives, there is a universal law that can be determined through reason. The postmodernist sees reason as a linguistic game to divide. Behind law, the barrister will see facts, that which actually happened, but the postmodernist only sees the law; concepts decided upon by the powerful.

Postmodernism is the rejection of Enlightenment modernist truth seeking. It is even a rejection of pre modernist truth seeking; the idea that behind the veil is the Will of God that we called to discover and enact. There is no reality, the postmodernists say. Reality is determined by the powerful.

Discrimination and the Power of Postmodernism

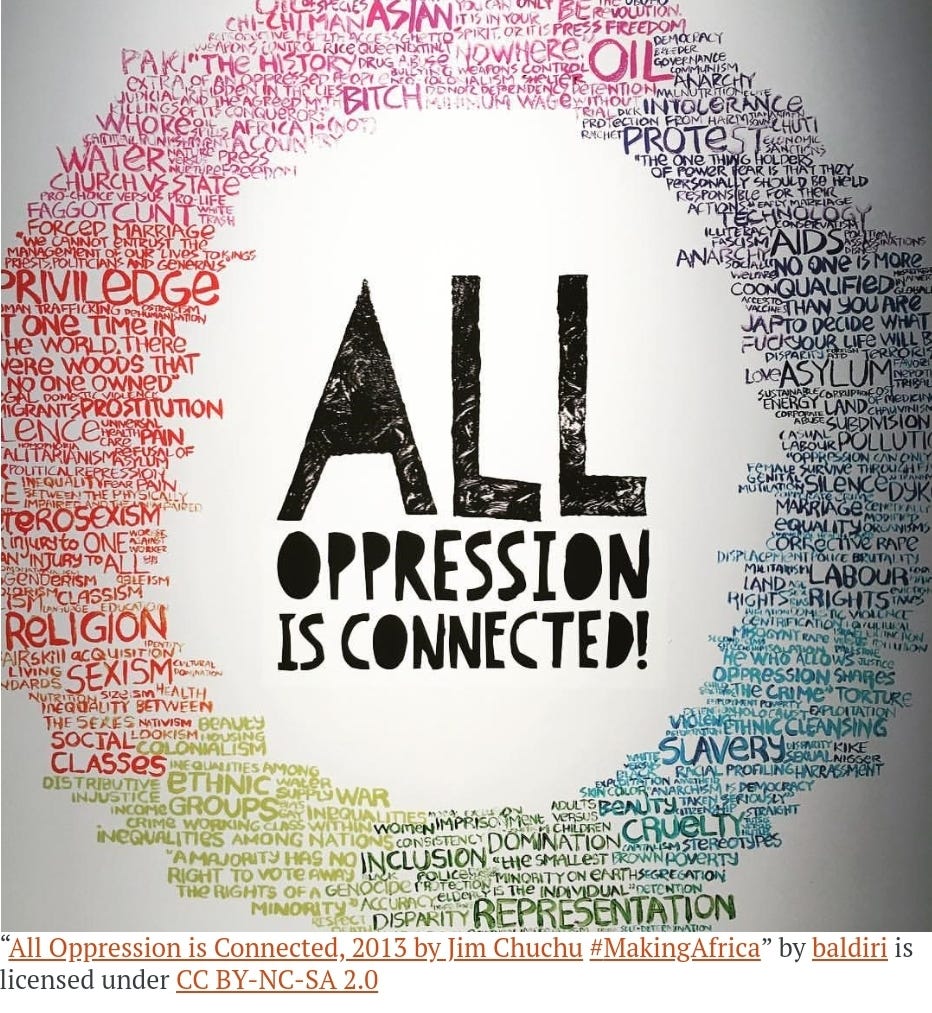

But though we must reject the idea that phenomena are unreal; that the world we see is a mere linguists game divided dichotomously by a cabal; we would do well to understand the motivation behind the postmodernist case. Derrida was correct about the nature of language: it divides the world into two9. Derrida was correct about the dangers of language: it divides the world into us and them.

Discrimination, racism, apartheid: all these are the illegitimate offspring of language. Once upon a time, we made a linguistic distinction between white people and black people, between Jews and Gentiles, between men and women. We did so innocently: to make sense of the world around us. But in doing so we were forced to define those in different categories differently. If we can distinguish between white and not-white, then there must be an inherent distinction between the two categories. If the world can be divided into two groups of people, men and not-men, then shouldn't we logically treat these two groups differently? Apartheid is a perfect example of racism through a human construct of language. The South African government discriminated betweens white citizens and the black underclass. But who is white and who is black? Were the “coloureds” white? The Jews? The Japanese? The Chinese? The government was forced into the role of an appellate court to enforce its racist policy. The palest white to the darkest black is a spectrum; the two groups of the Apartheid imagination didn’t exist. But through using the power of dichotomous language, the South African rulers made the unreal real.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Guerre and Shalom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.

![Living a Lie [Grand Narrative, Chapter 1.1]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!WsuS!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fca972889-18bb-4d7b-a496-c65cc50d7fa6_1035x696.jpeg)

![The Great Genocide Lie [Chapter 1.4]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!ji7r!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F04b0ba56-f1e5-4c92-a36a-85294ea84ccb_1014x735.jpeg)

![Hands off Churchill! [Chapter 1.5]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!6scA!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2e1bc915-fb46-419c-8929-1cd34dd68648_841x695.jpeg)

![Declaring War on Postmodernism [Part 1]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!mjFX!,w_140,h_140,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F8c9ffcc6-cbef-4ed3-8b71-4ffb2764e360_833x888.jpeg)