Revisionist Suez: Eden was right about Nasser

How to maintain international order in a post-imperial age

[Nasser “the new Pharoah”, retrieved from La Vanguardia]

Eden was to be proved absolutely right in his predictions about Nasser, just as he had in his assessments of Hitler and Mussolini in the 1930s. The dictator, emboldened by appeasement, went onto enact Arab imperialism in the Middle East from which we still suffer to this day. His sought a Union of subjugation with Syria, precipitated the fall of the Iraqi monarchy in 1958, effectively overthrew the Yemenite monarchy in 1962, involved his country in a “Yemenite Vietnam” against the remaining Arab monarchies, caused chaos in Lebanon and sought to establish himself as the undisputed leader of an Arab imperialist empire. The coup de grace was his attempt to destroy the State of Israel and condemn its population to a second Holocaust in the 1967 war.

Introduction: caricature history

20th Century is taught through caricatures. Churchill the hero. Chamberlain the villain. Imperialism bad. The United Nations good. George VI man of duty, Edward VIII man for himself. And above all “Suez was a humiliation for the imperialist Anthony Eden”. Today we deconstruct that myth and understand the issues raised by the 1956 crisis. For although Suez may appear as an affair long past, the issues it raised remain with us to this very day; chief among them who maintains international order in the post-imperial age.

Anthony Eden: Foreign Secretary Extraordinaire

Anthony Eden was one of the greatest statesman of his age, holding the post of British foreign secretary for a period of 14 years over three different decades. During some of the momentous moments of the 20th Century, Eden held one of the most important positions in world politics and performed his duties with unfailing dexterity. He spoke French, German, Arabic, Russian and Persian, the latter of which he adored as the “Italian of the Middle East”. In his youth it is said that he spoke French better than English and at Christ College, Oxford, he read Persian and Arabic, an ideal education, one might agree, for the life laid out before him. His knowledge of foreign affairs was unparalleled and he was idolised by his colleagues, not least by his successor Selwyn Lloyd, for whom languages were rather less of a natural gift.

Above all, Eden was a man of integrity and principle who resigned his post in protest at the policy of appeasement towards Mussolini’s fascist government. He then was one of only 39 Conservative MPs to abstain on the matter of Munich. Though this famous band of brothers was small in number, their effect on subsequent British political life was legendary. Among the 39 included Churchill and MacMillan, who, were it not for the failure of 1930s appeasement policy, would likely have faded into historical obscurity.

Background to Suez: Chamberlain & the Munich dilemma

But although Churchill and Eden rightly prophesied Hitler’s dictatorial breach of the Munich terms, we must give Chamberlain and his cabinet their due. Having suffered catastrophic losses during the Great War, the thought of a repeat showdown seemed too much to bear and in that they were supported by public opinion. The government knew that conflict with Hitler was possible, even probable, but to go to war over the Sudetenland seemed precipitous given the developing principle of self-determination. If the German-speakers of the territory wished to be reunited with the Reich, and the results of the Czechslovak democratic elections suggested that they overwhelmingly did, then would it be appropriate to deny them that right? If the allies were to invade the Sudetenland, the Rhineland or Austria, what would they have done next? Stayed as unwelcome occupiers? Cause regime change? Ultimately they would have had to leave and the status quo ante would have persisted.

We look at matters through the calm, unquestioning certainty of hindsight: the invasion of Prague, the bombing of the Blitz, the Holocaust. The horrors to come, at least that which was first listed, may have been foreseeable - and Churchill, Eden and MacMillan are to be praised for so doing - but it is unclear what actions Britain could have taken that would have been effective, long-lasting or even possible, given our meager 10 army battalions compared to Belgium’s 20 and the Soviet Union’s 500. It was only with the utter catastrophe brought upon us by Hitler in the coming years that the Fuhrer’s end was to become acceptable, not only in the eyes of Britain and the allies, but in the eyes of Germans themselves.

Given the above, Chamberlain’s government felt unable to take a stand in 1938. Nonetheless, they sought to prevent the following, unacceptable reality, namely that Germany be permitted to conquer the Sudetenland in a show of brute force. In a nod to the post-war, post-imperial order, they hoped that the handover could be arranged in an orderly fashion according to the norms of developing international law. If the Reich were to take the territory, it needed to be based on the principle of self-determination alone. Munich was thereby a matter of agreeing handover procedure and setting a precedent for a hoped international order.

Ultimately Chamberlain’s bid failed. Eden and Churchill had predicted the results of his efforts and should be garlanded accordingly. They were principled in their opposition to kowtowing to militaristic dictators. But to label Chamberlain a weak fool would be unfair; an armchair judgment of hindsight that falls into the trap of caricature. The PM knew that his efforts would likely fail; in the car from Heston airport (of “peace in our time” fame), he commented to an advisor that he hoped for the best, but feared the worst. But he wasn’t willing to sacrifice British lives on the pyre of self-determination; the time for inevitable conflict would have to wait. You can agree with him or (more likely) disagree with him. But his attempt to shackle murderous, antisemitic dictators (however detestable) to a rules-based order remains a challenge up to modern times; and the solution is yet to have been found.

Maintaining international order in the age of imperialism

In the days of imperialism, it was Europe, and above all Britain, that assured international peace. Despite their incessant squabbling, the European powers (including the Ottoman Turks) often met at summits to resolve disputes and agree upon world boundaries. The United Kingdom with its supreme naval power had the responsibility of controlling the world's oceans and by doing so it ensured global peace. Whilst armed conflicts continued aplenty among the far flung, native tribes, the arterial waterways - the Suez Canal, the Bab al-Mendez Strait, the Straits of Malacca among them - remained open to world trade and the seas were kept free from unwanted piracy.

It is easy to look at this with caricature; to make incendiary claims such as “Britain raped India”; but to do so necessarily underplays the advantages of Great Power stability. There is no doubt that Britain and her European neighbours benefited greatly from the prevailing state of affairs. Hegemons always benefit; but that is as much a characteristic of the modern as that of the pre-modern. The European Union is a German economic empire in all but name with European interest rates set to favour the interests of German industry; the effects on Greek enterprise be damned. Indeed Britain was forced out of the pre-Euro Exchange Rate Mechanism for its failure to align itself adequately with Bundesbank economic interests. But the EU member states submit to German economic domination for their own general benefit, above all the maintenance of peace in Europe. I repeat: the hegemon always places its advantage above all else but it does so with positive collateral effects: order, peace and stability.

The British Empire was the 19th Century European Union. Peace, freedom of movement, freedom of trade and economic opportunities in return for submitting to the preferences of the world power. With the dawn of the 20th Century, imperialism began to be called into question, above all the issue of ruling over peoples who wished to forough their own path. Self-determination became King. But with eventual decolonisation came the concomitant disadvantage: a peaceless, orderless world where wayward dictators hold sway. It was this issue that Chamberlain was forced to grapple with at Munich. And it returned to haunt Eden with a vengeance at Suez.

The challenge of decolonisation for world peace

Anthony Eden was no backward looking imperialist. He was entirely aware that the decolonisation was going to accelerate in the coming years and that there was an appetite for autonomy among the imperial subjects of Empire. He neither sought to stand in the way nor the reverse the process. Sudan was even to become independent under his stewardship (1954), contrary to Labourite fears that the Conservatives would be pro-Empire belligerants.

Rather, Eden's goal was to secure international order in a world of increasingly divergent interests. Shortly before his death Churchill told an acquaintance that his life’s work had been a failure with the British Empire no longer holding sway to maintain the peace and while Eden issued from a less Victorian generation, he shared his mentor’s passion for global stability. Hitler and Mussolini had tested that ideal and though they were defeated amongst unprecedented bloodletting, the challenges they posed remained.

The United Nations had seemed to some as a replacement for Empire; the great powers acting in concert to resolve international security challenges. In its early days it was marginally more successful than it is today, but only because the Korean War had began during a period of Soviet boycott (13 January until 1 August 1950). With the USSR absent from proceedings, the field was open to the United States and its allies to send their defence forces upon invasion by North Korea. But the swift action of the allies in 1950 only underlines the benefits of Empire for international order. Only when the United Nations was left as an imperial tool in the hands of America was it both responsive and effective. The moment bipolarity returned to rule the body, gridlock and impotence was the result.

Moreover the Korean War marked a moment when Western Europeans, notably Britain’s left-wing, socialist government, were keen to react in Korea to ensure continuing American global engagement. With the return of American isolationism as probable as ever and the risk to Western European defence never more precarious, it was vital for Britain in particular to step up to support America’s East Asian goals. So important was the continuing involvement of America in world affairs, that Britain pledged to rearm to the tune of 12% of its national budget (imagine that now!), a commitment that PM Attlee was determined to realise irrespective of its political price. And the price was high. With so many resources dedicated to defence, charges were proposed in the newly-born National Health Service, leading to the resignation of Aneurin Bevan and Harold Wilson. The divisions lost Labour the upcoming elections. But with the Russians so very nearly at the door, defence of the continent demanded it. Briefly put, with the decline of Britain’s Empire already in progress, a new Empire needed to take its place to hold the fort. But would America play ball?

With imperialism on the wane and America ever reluctant to take its place, who would be responsible for maintaining the free passage of trade on the world’s oceans? Who would be charged with keeping piracy at bay and (to use a modern example) stopping the Houthis throwing missiles at international shipping? It had always been Britain that had stepped up to the plate, controlling the coast of Yemen’s Aden, Oman, Kuwait, Iraq, Cyprus and Singapore to ensure the free flow of trade, but who would do it now? The Bab Al-Mendeb and Hormuz straits had to be secured. And so did the Suez Canal. It wasn’t a matter of occupying a foreign people, rather the necessity of transporting fuel, and it couldn’t be left in the hands of erratic dictators.

[Blockade of the Suez Canal, retrieved from Historyextra.com]

Protecting the Suez Canal waterway: A test in a world of dictators

That the Suez Canal resided in Egyptian sovereign territory was never in dispute. Nor that the Egyptian people, independence since 1922, wished to be in control of their own affairs. The United Kingdom never had any designs on the Egyptian territory per se, but wished to ensure international control of important waterways; and not merely for their own good but for the good of all. Following Israeli independence, the Jewish State had wished to use the Suez Canal for the necessities of trade and as an international waterway, they had every right to demand this. The state of war between Israel and Egypt was singularly irrelevant in this demand, but the Egyptians, despite United Nations demands, refused to comply. This was the example par excellence of why strategically important international waterways cannot be left under the control of petulant, third world dictators no matter their sovereign claims.

Britain sought to influence Egyptian affairs through the installation of a sympathetic monarchy. This policy continues to work to this day in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, but it failed in Iraq and the King fell to a similar fate in Egypt. Part of their arrangement was to establish a sector of control around the Suez Canal. This was no mere buffer zone; it extended all the way from the Red Sea to within spitting distance of Cairo. A modern commentator may condemn this as an infringement of Egyptian sovereignty and colonialism by another name. Yet it not only secured the safety of shipping on the Suez Canal but (for practical purposes) it ensured the peace between Israel and Egypt. Britain was in effect a friendly neighbour of the Jewish State.

The Tripartite Agreement, Israel and the effect of Britain’s disengagement on Middle Eastern security

“Every commander should be prepared and prepare his troops for unavoidable war with Israel in order to achieve our supreme objective, namely, annihilation of Israel and its complete destruction in as little time as possible and by fighting against her as brutally and cruelly as possible.” (When the British invaded Egypt in October, they found the following operation order to Egyptian commanders, dated 15th February 1956)

Under the so-called Tripartite Agreement of 1950, the USA, UK and France agreed to guarantee the territorial status quo that had been determined by the 1949 Arab-Israeli Armistice Agreements. They engaged to “immediately take action, both within and outside the United Nations, to prevent such violation.” It was a classic class of Western imperial powers using their influence to prevent further violence, secure the current borders and maintain the peace, even with the somewhat optimistic aim that the Arabs and Israelis would unite against the Soviet threat. Despite justified Israeli protestations that they were denied vital arms under the accord - whereas the similarly restricted Arabs could procure them by other means - it is unarguable that if Britain had remained in control of the Canal and its environs, that neither the 1967 nor 1973 wars would have taken place with all their attendant consequences. For all the benefits of the 1977 Israeli-Egyptian peace agreement, British control of the Sinai would have ensured Israeli security to a far greater extent and the Gaza War we have seen today would have never taken place. Yes the 1950 agreement was “imperialistic”, but it would have ensured a lasting Middle Eastern armistice. It merely underlines the importance of the engagement of world powers in keeping the peace.

Yet the Egyptian monarchy fell, so Eden, realistic as ever, understood the need to build a relationship of trust with the new nationalistic powers. Far from the absurd warmonger caricature of legend, Eden - under great pressure from the Conservative right flank - took great risks for the continuing co-operation of Egypt. Indeed although Harold Macmillan eventually succeeded Eden following the fallout from Suez, it was he that was harshest in pushing for action against Nasser. At one point, he even threatened to resign his cabinet post should the perceived appeasement of the Egyptian strongman continue. As for Eden, he oversaw the 1954 Anglo-Egyptian Agreement which agreed upon the phased evacuation of British troops from their Suez Canal base with the proviso that the British had a right to return (for a seven year period) should the need arise.

However Nasser didn’t use his country’s diplomatic success for peace. Instead he launched largescale Fedayeen terrorist operations from Egyptian territory into Israel, causing mounting fear among the Israeli populace. The Egyptian government was even responsible for supervising the establishment of formal Fedayeen groups in Gaza and Northeastern Sinai. Plus ca change. He also planned a full scale invasion of the nascent Jewish State; during short lived British conquest of the Canal during the 1956 crisis, soldiers from the British forces found commands from the dictator to “annihilate” the State of Israel with “cruelty”1. The British withdrawal in 1954 was precisely what Harold MacMillan had feared: appeasement for a new age. Instead of ushering in the sunny uplands of decolonised freedom, the emboldened dictator had used the disengagement plan to launch his antisemitic wet dreams. Israel knew it had to respond against Egypt’s new and dangerous government and under the protective air umbrella of the Anglo-French operations of 1956, they acted decisively.

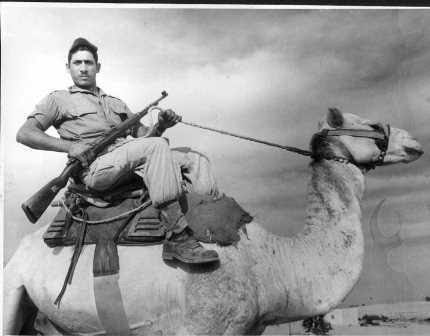

[Israeli soldier on a camel, retrieved from zionistarchives.org]

The Nasserite Hitler: The Challenge of Arab Imperalism

But it wasn’t just Israel that was under threat from the new appeasement: it was the entire Arab world. At the time, it was Nasser-led Arab imperialism (not British) that was spoken of in Arab capitals as the Middle Eastern colonial force. The Iraqi govenment was particularly threatened by the warmonger in Cairo, with the Egyptian-based “Voice of the Arabs” radio station being used to advocate for the overthrow of the Baghdad regime. The Iraqi, Jordanian and other monarchies quivered in fear at Nasser’s new Arab nationalism and Britain was deeply concerned about its necessary destabilising effect on international waterways and the flow of oil. As with Hitler at Munich, whose calls for Sudenland annexation was tolerated on the basis of theoretically justifiable claim of self-determination, so had Nasser’s claims been tolerated on the basis of sovereignty. But as with Hitler he was (inevitably) not a man of his word. The 1954 agreement was a pretext for violence, conquest and regional hegemony.

The comparison was not lost on contemporary decision makers. The Secretary General of the UN had compared Nasser’s speeches to those of Hitler and Eden himself had compared the Egyptian to Mussolini. History was repeating itself; and the man that had resigned over Italian appeasement - and was lauded for doing so by the light of history - felt obliged to take a stand once more. The mere mention of Nasser’s name made him shake violently with rage.

But though politicians from MacMillan to the UN Secretary General knew that war was soon for the Middle East by the hand of the Nasserite Hitler - and that Jewish genocide was an aim he shared with equal passion - the question once more was when to act. Should the West wait for the “invasion of Prague” or take a stand in the moment based on the lessons of history. Chamberlain had chosen to stall and was damned by history. Eden was to act with immediacy and was damned likewise. In world leadership, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

Chamberlain v Eden: Damned if you do, damned if you don’t

Chamberlain at Munich and Eden at Suez were faced with the same dilemma. How to deal with evident ultra-nationalist bullies who hadn’t quite crossed the line into unequivocal illegality. Hitler had entered the Rhineland in defiance of Versailles but could argue it was foreign occupation. He then entered Austria but could claim native support. Next he moved on to the Sudentenland and could call upon self-determination. The militaristic, antisemitic nature of his regime was plain for all to see, but by still having certain cards of international law to play, he could see off the threat of Anglo-French intervention.

In the same vein, Anthony Eden was faced with a fascist, antisemitic regime that threatened the international order and exploited the British appeasement of withdrawing from the Suez Canal Zone. As in the 1930s, Nasser had used the British response to attempt to terrorise a neighbour (Israel). As in the 1930s, Eden couldn’t count on an instinctively, isolationist United States that - this time - was embroiled in a domestic election campaign. Maintaining the peace was Eisenhower’s trump card and he wasn’t going to sacrifice it on the pyre of some “far off country he knew not of”. Yet as with Hitler Nasser had certain cards of international law to play: anti-colonialism, self-determination and above all legality under property law. His nationalisation of the Canal was, strictly speaking, legal. The company was an Egyptian company, registered under Egyptian law and he was prepared to pay the shareholders for his purchase at current market prices. The way he took over the company’s property - with force and in the dead of night - failed the smell test: as left-wing British politician Aneurin Bevan was to comment, it had more resonances of an Ali Baba raid than a legitimate market purchase2. Nonetheless being legal on paper, did it give Eden a pretext to take action?

There isn’t a “right answer” given that the Eden’s and Chamberlain’s opposing approaches have both been cartoonishly subject to historical criticism. Nonetheless, Eden (and Churchill and MacMillan) didn’t want appeasement 2.0. The Americans, in full kick the can down the road mode, arranged a Munich-like summit to discuss “6 principles” to end the standoff and ensure continuing international access to the canal. Eden played ball, but realised from his actions since 1954 that Nasser was “not a man of his word”. Whatever guarantees Nasser were to give, he would inevitably follow the path of Hitler endangering international peace, threatening international trade, bankrupting the British economy and seeking to undertake a second Holocaust. Following his long-standing moral principles and trying to learn from history, Eden was determined not to make the second mistake twice.

The British had employed various methods to force the Egyptians to back down, notably withdrawing its experienced (canal) pilots from service on the waterway. But all pacific attempts had failed. Realising that the threshold for intervention under international law had yet to be met (but was nonetheless needed to prevent a repeat of the mistakes of appeasement), he colluded with France and Israel to take back international control of the Canal and thereby (hopefully) precipitate the overthrow of Nasser. As is now common knowledge, Israel was to invade from the West, “forcing” the British and French to intervene to keep the two sides apart and maintain control of the Canal.

Failure: A Question of Timing

Unfortunately the plan was to fail for three, important reasons, neither of which was Eden’s “breach of international law” or desire to enact regime change. After all, the British had engineered the overthrow of Iran’s Mohammed Mossadegh only three year’s previously with complete American approval; indeed involvement. The US would continue this policy in Guatemala, Panama and latterly Iraq, showing that criticisms of this nature are pure American hypocrisy.

The first reason that Britain was forced to withdraw was logistical. Given that the British were officially responding to an Israeli invasion they could hardly launch their naval response until the Israelis had crossed the border. Unfortunately the Israelis completed their conquest of the Sinai rather too quickly, meaning that by the time the British forces were in place to enable an amphibious assault on Port Said their raison d’etre for being there was no longer credible.

This leads to the second reason: The American decision, in the midst of an election season, not to support the British cause. They failed to prop up Sterling in the ensuing economic crisis, leaving the UK with little choice but to withdraw her forces. On one level, it was all a question of miscommunication with the statements of decision makers in two jurisdictions misunderstood. The US Secretary of State was rather more supportive of Eden’s case than the President but as a mere appointee of Eisenhower, with no political base of his own, his position was merely one of communicating the Presidental policy. Unlike the UK Foreign Secretary he had no autonomous decision-making capacity of his own, a fact that those enmeshed in the Westminster system failed to understand. Meanwhile the Americans didn’t understand the importance of the Chancellor of the Exchequer in the British system where he is the number 2 in government (quite unlike the Finance Ministers in America and Europe); the importance of Chancellor MacMillan to decision-making was misunderstood when he was present in Washington.

Ultimately though, it is clear from American documentation that has come to light, referred to by Professor Vernon Bogdanor, that if the Suez Canal had been captured quickly, the Americans would have supported the action as a fait accompli. But with the aforementioned need to maintain the pretence of response to Israeli invasion that simply wasn’t possible. Ultimately America sought a ceasefire in the Security Council, vetoed by the UK and France, and when they failed, they sought a ceasefire declaration in the UN’s General Assembly. Aside from Britain, France and Israel, only Australia and New Zealand supported Eden’s Churchill over Nasser’s Hitler. Not for the first time in Middle Eastern affairs, the Americans - and the world - sought ceasefire over supporting the forces of order against those of chaos.

The third reason follows directly from that outlined above. Even if Eden and his French counterpart had succeeded in their aims, they would have been faced with a hostile Arab population who would have seen them as occupiers. There would have been guerilla attacks ordered against them on a daily basis, gleefully arranged by a dictator experienced in terrorism, and unlike the Israelis, the victims would have somewhere to go: home. This “Arab resistance” (ie mindless violence) would have been supported by the world community, even possibly by the “anti-imperialist” Americans, and ultimately the Anglo-French force would have had to leave, precisely as it had in 1954. If Chamberlain had invaded Germany in 1938, prior to the invasion of Bohemia and Morevia, he would have faced exactly the same problem: terrorism from an unwilling population that would have supported the Nazi regime. The Anglo-French army would have had to leave and Hitler would have survived to fight another day. Perhaps Chamberlain’s appeasement gave the coming total defeat of Hitler legitimacy? As I say, you are damned if you do and damned if you don’t.

[Hitler and Chamberlain at Munich 1938. Image retrieved from a New York Times article entitled “Neville Chamberlain, A Failed Leader in a Time of Crisis”. Anthony Eden was abandoned by teh Americans for making the precise opposite decision.]

Historical re-evaluation: Prophetic Eden, Nazi Nasser and our lawless world

Eden was to be proved absolutely right in his predictions about Nasser, just as he had in his assessments of Hitler and Mussolini in the 1930s. The dictator, emboldened by appeasement, went onto enact Arab imperialism in the Middle East from which we still suffer to this day. His sought a Union of subjugation with Syria, precipitated the fall of the Iraqi monarchy (that, relatively speaking, protected its minorities) in 1958, effectively overthrew the Yemenite monarchy in 1962, involved his country in a “Yemenite Vietnam” against the remaining Arab monarchies, caused chaos in Lebanon and sought to establish himself as the undisputed leader of an Arab imperialist empire. The coup de grace was his attempt to destroy the State of Israel and condemn its population to a second Holocaust in the 1967 war. He mercifully failed. But the consequences of the British withdrawals in both 1954 and 1956 and the subsequent Nasserite aggression, fueled by the fiery support of the “Arab Street”, are directly responsible for the unstable situation in the West Bank, Gaza and throughout the Middle East today. America’s failure to fully support Eden’s Britain, in acquiescence of an Arab Hitler who acted precisely like the German, was unforgivable. The only difference was that, by that point, the Jews had guns.

Beyond its historical consequences, the Suez Affair highlights the dangerous absence of a world order in the aftermath of imperialism. When the Middle East and its waters had a hegemon - Turkish or British - peace could be maintained and international order ensured. Even regarding Israel, had the the 1950 Tripartite Agreement been enforced beyond 1954, through Britain maintaining its position in the Canal Zone as the Conservative right-wing rebels had called for, then the Jewish State’s borders would have been secured. [It is indeed telling that Jordan, with its British imposed monarchy still in control, provides Israel’s most solid border.] Yet with imperialism out of fashion, there is none to maintain safety on the seas, the free flow of trade and the peace of warring tribes. The United Nations, bar a brief moment in the Korean Sun, has been largely ineffective - or worse - in dealing with international problems; its authoritarian membership make it so. So we left to ask the following questions: though we all agree with autonomous self-government in day-to-day affairs, isn’t it time for a benign imperial force to return to control the major world arteries? Should not America (or, perhaps better, a British-Australian-New Zealand-Canadian-Carribean-Indian-Singaporean supranational federation) lead a newly formed “United Nations” of the “willing free” to maintain international order? Indeed aren’t we obliged to do so?

Whatever your opinion on these questions, let us be clear on this: Anthony Eden was one of the greatest, if not the greatest, statesmen of the 20th Century. He foresaw Mussolini. He foresaw Hitler. He foresaw Nasser. Far from a British imperialist in its negative sense, he sought to use benign British power to keep aggressive Arab and German imperialists at bay. Where he was supported by the world, international order was restored. Where the world stabbed him in the back, the result was bloody Middle Eastern violence. Perhaps the time wasn’t ripe to act against Nasser, but isn’t that what they said at Munich? We are still living in the shadow of Anthony’s dilemma - how to control genocidal dictators and international waterways in a post-imperial world - and only when we happen upon the correct solution, will we finally arrive in Eden.

May Anthony Eden be remembered once more as a great man of history. I, for one, am an Edenist.

Sources:

Bogdanor, Vernon (2016), The Suez Crisis of 1956, Gresham College, Youtube

Bogdanor, Vernon (2012), Britain in the 20th Century: Appeasement, Gresham College, Youtube

The Other Side of Suez, BBC Four, Mohamed Omran channel, Youtube

The Lebanese Civil War, Casual Historian Channel, Youtube

What caused the Algerian Civil War, Casual Historian Channel, Youtube [Regarding the French motives for involvement in Suez. Essentially Nasser was funding the FLN.]

Olson, Lynne, Neville Chamberlain: A Failed Leader in a time of crisis, NYT, retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/10/books/review/tim-bouverie-appeasement.html

When the British invaded Egypt in October, they found the following operation order to Egyptian commanders, dated 15th February 1956: “Every commander should be prepared and prepare his troops for unavoidable war with Israel in order to achieve our supreme objective, namely, annihilation of Israel and its complete destruction in as little time as possible and by fighting against her as brutally and cruelly as possible.”

“If the sending of one’s police and soldiers into the darkness of the night to seize someone else’s property is nationalisation, then Alibaba used the wrong terminology.” (Aneurin Bevan)

Daniel Clakke-Serret is very knowledgeable. His posts are comprehensive

Thank you so much - I feel like I just finished a year-long master class, though obviously this will require several more readings.