Three legal opinions on International Law

Our resident international legal expert answers questions on the Middle East

FOREWORD FROM THE EDITOR [Daniel Clarke-Serret]

Guerre and Shalom believes in the power of public discourse. Having written a number of articles challenging the very basis of the international legal system and the functioning of the ICJ, it is only right that we feature a writer with a different view. Whilst critical of the imperfect reality of the international legal system. our guest contributor Shlomo is nonetheless convinced of its overall necessity. Notably, he is a big defender of the principle of international human rights.

Shlomo Levin's background is fascinating and very possibly unique. He received ordination from The Israeli Chief Rabbinate and Yeshivat Hamivtar, and also holds an M.A. in International Law and Human Rights from the United Nations University for Peace in Costa Rica. For many years he served as a Rabbi, but now writes about human rights issues of particular interest to Israel and the Jewish community. He is the author of the Human Rights Haggadah.

I have included three of his legal opinions (the 3rd for paid subscribers only). And we begin, perhaps unsurprisingly given Shlomo's background, with a lesson from Maimonides for the ICJ.

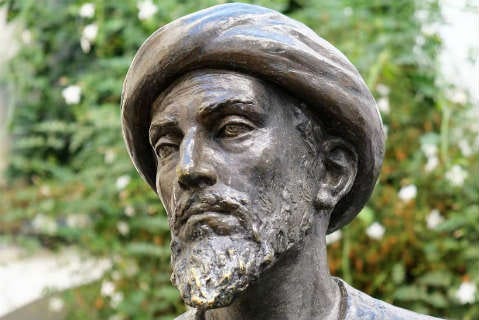

[Image: the statue of Maimonides in Córdoba, Spain.]

Three legal opinions on International Law by Shlomo Levin

Opinion 1: When Justice is Too Much to Ask: A lesson from Maimonides for the ICJ

The Jewish legal tradition is clear about theft. If someone steals an object, they have to give it back. Of course sometimes that is not possible - let’s say someone stole wood and used it for a fire. In this case, since the thief can’t return something they’ve already consumed, they pay money instead. Everything seems straightforward.

But Maimonides, the great 12th century Jewish legal scholar and philosopher, considers another scenario. Let’s say the thief stole wood, but rather than burn it used the ill-gotten plank to construct the foundation of his home. Now in order to return one small stolen beam the thief would have to dismantle his entire house! Maimonides says that according to the letter of the law that is in fact what should be done. But already in the times of the Talmud, the rabbis realized this could become an insurmountable obstacle to repentance. So they decreed that in such a situation the thief could keep his house intact and just repay what the wood was worth. They understood that insisting the thief suffer such a large loss meant he would likely just dig in his heels to deny the crime and refuse to make amends at all (Laws of Theft 1:5).

In its recent advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice determined that Israel’s continued occupation is illegal and therefore Israel must withdraw from the West Bank, Gaza, and East Jerusalem as rapidly as possible. The legal logic is clear- the occupation is an internationally wrongful act which must be righted.

But consider the impact a complete withdrawal would have on Israel. Due to the settlement process which has gone on for many decades, by now 700,000 Israelis currently live in the occupied territories and East Jerusalem. While those settlements may be illegal, moving that many people would require resources clearly beyond what the Israeli government can muster, to the extent it is at this point even feasible at all.

The new, $2 billion dollar high speed train from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem passes through a corner of the occupied territories as it connects with an elaborate span of bridges and tunnels. Rerouting would obviously be extraordinarily difficult, if a possible alternate route could even be found.

Jerusalem’s multi-billion dollar light rail , opened in 2011, travels right through the Palestinian side of the city and is now integrated into Jerusalem’s transportation system. Even if it would technically be possible to redivide the city, it’s hard to see how that could be done without ruining the costly public transportation infrastructure hundreds of thousands of Jerusalem residents depend on.

The ICJ says all this was built illegally and international law requires that it be removed. But even those who agree with the ICJ ruling must admit one thing: it is not being implemented by Israel, and in practical terms has had no effect.

Of course one can blame Israel’s current government, which has scorned the opinion and made clear that it has no intention of letting some judges in the Hague tell it what to do.

But what if Israel had a government that was of a mind to take the ICJ ruling seriously? How would even the most acquiescent government react if told that the law requires it to take steps that would utterly bankrupt the country and are hardly even possible for it to do? Contempt and disparagement of the court would still be the most likely outcome.

The Talmud (Baba Kama 94b) tells the story of a man who desired to repent after a lifetime of thievery. His wife said to him, ‘Dummy- if you repent you will have to return everything you have, as even the belt you are wearing is not rightfully yours.’ Due to his wife’s advice, the man changed his mind and did not repent. Based on this the Rabbis declared that ideally one should not accept a stolen item back even when a robber offers to return it, in order to make repentance less onerous and thereby make it easier for people to change their ways.

Of Course Palestinian rights must be respected and illegal occupation brought to an end. But when international law takes a maximalist, punitive position towards Israel progress becomes less likely.

ICJ President Nawaf Salam wrote in his separate declaration accompanying the court’s decision:

one must question the opposition that some appear to draw between peace and law. . . international law and justice unquestionably provide a means for the pacification of international relations. By stating the law, the Court provides the various actors with a reliable basis for a just, comprehensive and lasting peace. . . . I am convinced that a negotiation process that is shorn of legal and equity considerations would carry within itself the seeds of future conflict. (paragraphs 65-66).

He is undoubtedly correct that law and equity must be at the center of any durable peace. However, as the Rabbis discovered, a focus solely on justice without regard for the impediments to repentance justice may create can also be counterproductive.

For International law to be respected and followed, it has to render decisions that its subjects are reasonably able to follow. Law will be a tool for peace between Israel and the Palestinians when it offers Israel a viable path to bring itself back into good standing with the international community. It invites scorn and irrelevance when it makes demands Israel cannot fulfil.

Opinion 2: Self Determination: The Important Question That Hasn’t Been Asked

The international legal principle underlying the Palestinian claim to statehood is the right of self-determination. This right is well established, and is even mentioned in the United Nations Charter. The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which has been agreed to by 174 countries, begins by stating, “All peoples have the right of self-determination. By virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.”

In its recent advisory opinion, the International Court of Justice decided that Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territory violates the Palestinian right to self-determination. This was a key basis for the court finding the continued occupation illegal (see paragraphs 230-243).

But there is an important question which seems has largely been neglected. Most rights come with responsibilities. Does the right to self-determination come with any responsibilities at all?

It’s well known that some portion of Palestinians and their leadership are devoted to the destruction of Israel. They may exploit control of any territory Israel relinquishes to further attacks pursuant to that aim. Does this threat to exploit self-determination for purposes that are illegal affect the ability to exercise that right?

In its advisory opinion the International Court of Justice assumed that it doesn’t. Judge Tladi of South Africa made that explicit in his accompanying declaration, stating:

security concerns cannot even serve as a balance against rules of international law and certainly not against peremptory norms. Thus, the notion that the Palestinian right of self-determination must be balanced with, or is even subject to, Israeli security concerns is incongruous as a matter of international law (paragraph 44).

But can this really be so? Is self-determination such a fundamental right that even security can’t touch it? That no prospect of it being abused to cause harm to others can stand in its way?

International law does in fact put limits on self-determination. Most prominent, self-determination cannot be exercised in a way that interferes with the territorial integrity of an existing country (see for example UN resolution 1514 of 1960). This is an extremely significant restriction, as most self-determination movements aim to secede and take territory from an existing state.

So what about using self-determination not to violate the territorial integrity of a state in the process of the exercise of the right, but rather to enable military action designed to take territory from or even destroy an existing state thereafter?

An important problem is that assessing future action requires speculation. One could argue that mere suspicion, even if based on some evidence, that a people claiming self-determination will thereafter embark on a war of aggression shouldn’t be enough to annul an important right. Maybe statements of intent are just fiery rhetoric voiced out of frustration and the threatened aggression won’t ever materialize. In our terms, perhaps whatever subset of the Palestinian population that genuinely desires a peaceful two state solution would win out. Maybe those that claim today they will settle for nothing less than Israel’s total destruction will cool off if they are able to exercise self-determination and those threats will be revealed as only angry bluster.

But should there be a point where this speculation reaches a level of certainty that it has legal consequences? For example, consider criminal law. Not only are some acts criminalized, but the attempt to do them is criminal too. This means we have set a standard to take us from speculating about what a person is attempting to do to proving it. Talk isn’t enough. But if a person not only says they want to commit a crime, but also takes concrete actions towards facilitating it, that can be enough to create criminal liability. Mere diary entries about wanting to shoot the president won’t land you in jail. But purchasing a gun and sneaking around outside the White House might.

So too here. Maybe just speeches about wanting to destroy Israel should be shrugged off. But Hamas using Gaza after Israel’s withdrawal to construct missiles, fire at Israeli territory, and carry out the attack of October 7th? Israeli fear that Palestinian exercise of the right to self-determination may directly result in severe harm to its security is certainly well founded and real.

So here is a question we need to ask. What happens when a people is denied exercise of a fundamental right, but there are strong grounds to believe that if the right would be fulfilled a subset of that people will attempt to use it to perpetrate abuses that deny the rights of others? Is this a non-factor, as judge Tladi believes? Does this concern attach conditions to how the right is exercised, such as by legitimizing a demand for security guarantees as it is implemented? Is there a threshold of certainty that must be met for this to be a factor?

To the best of my knowledge, these are matters that have not yet received sufficient attention or deliberation under international law. In order for self-determination to become a fully fleshed out, workable right these questions will have to be answered. In the meantime, we’ll have to make up our minds about it for ourselves.

Opinion 3: The attack on Nasrallah and International Law

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Guerre and Shalom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.