Beyond Chanukah: The Hellenized Jews of Alexandria

Revising our perspective on the contribution of non-Hebrew speaking diaspora Jews

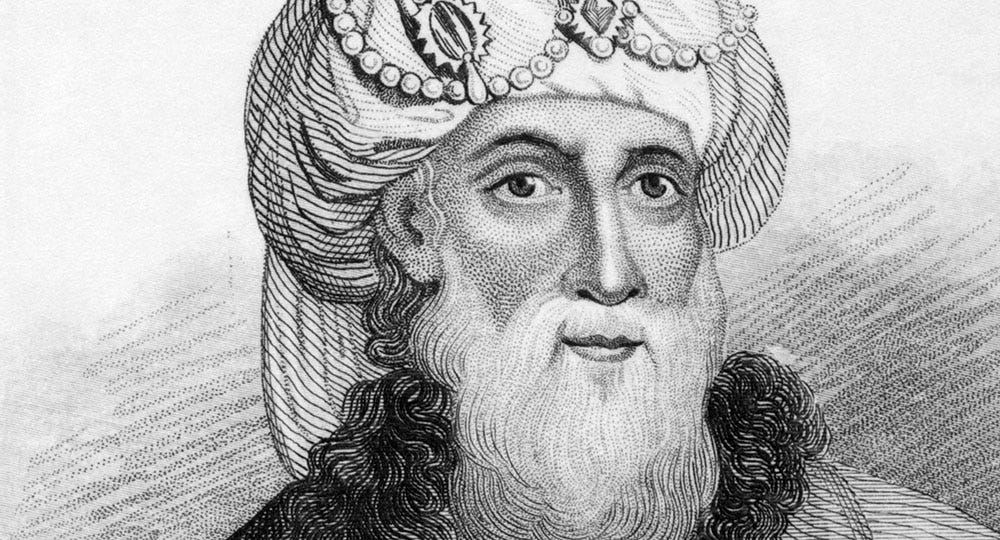

[Josephus: Hero or villain? Image retrieved from https://israelmyglory.org/article/josephus-jewish-war-correspondent/]

Foreword by Daniel Clarke-Serret (editor):

Once more, we have the pleasure of publishing a piece from our regular guest contributor Eli Kavon: Rabbi, historian and essayist from Palm Beach, Florida. If you too are a seasoned writer and would like to appear on Guerre and Shalom as a guest contributor, feel free to contact me. Don’t feel limited on the topic. Fellow guest contributor Vaishnav Sunil has written on the topic of immigration, Einat Wilf has written about the United Nations and Richard Neat has written about travel. The qualification for publication is an interesting, well-written article that makes us think. One of the key goals of this newsletter is to smash open the echo chamber walls and for that we need multiple perspectives and writers from different backgrounds. I look forward to hearing from you.

I now proudly present Eli’s written piece related to Chanukah which gives us a different perspective on the Hellenized, educated Jews in the Roman-era diaspora. Although they wrote in Greek, their attachment to the Jewish story was unquestionable. Rather like English-speaking writers on Substack today…

One hopes that revising our understanding of this period could lead to a greater level of mutual respect between Israelis and their diaspora cousins.

I have also included a second, longer essay from Eli on “Chanukah: The Maccabees in the Zionist Imagination”. This is only available to paid subscribers. In this week until Chanukah there is a 60% discount on annual paid subscriptions (NOW ONLY £25 / $31). DON’T MISS OUT!

“Beyond Chanukah: The Hellenized Jews of Alexandria” by Eli Kavon

The caricature of the civil war that was a major component of the events that we celebrate on Hanukka is one of loyal, Jewish, Torah-true guerillas fighting against Hellenized Jews who were all turncoats who rejected Judaism. It is time to discard this portrait of Hellenized Jews as all wrestlers in the Greek gymnasium who underwent surgery to reverse their circumcision. In fact, one of the reasons Judah Maccabee succeeded in liberating Jerusalem and rededicating the Temple was the support Judah received from moderate Hellenized Jews who were acculturated and influenced by Greek philosophy and culture but nevertheless were loyal Jews who rejected the extreme edicts and worldview of Seleucid King Antiochus IV. The reality of the ancient world is that of millions of Jews living in the Hellenistic Mediterranean and Middle East who made significant contributions to Jewish life and thought despite knowing no Hebrew and having to read the Hebrew Bible in the Greek Septuagint. These Hellenized Jews, like many Jews throughout our history, were highly acculturated but did not assimilate and forfeit their Jewish identity and faith.

The greatest Jewish community in the ancient Hellenistic Diaspora was in Alexandria. In the Egyptian port city founded by Alexander the Great during his conquests of the known world in the 4th century BCE, 250,000 Jews were a significant part of the population by the Roman period in the 1st century CE. First under the rule of the Greek Ptolemies, then under Roman domination, Jews occupied careers from bankers to artisans. The Jewish intellectual elite adopted the genres of Greek literature—the epic poem, drama, the writing of history, the penning of the novella and philosophy—always writing in Greek but focusing on Biblical and Jewish themes. In this highly acculturated environment, Jews did not assimilate but asserted their identity, especially when faced by the hatred of the Greeks when Rome ruled Alexandria. This animus would later lead to rebellion.

The greatest figure to emerge from the elite of the Jews of Alexandria was philosopher and political activist Philo. The scion of a wealthy banking family with ties to the monarchy in Judea, Philo read the Torah as both Law and Philosophy. While he did read the Torah from a literal standpoint and was a pious Jew, Philo added a layer of philosophical allegory on to the text that understood anew the meaning of the text. He reconciled the Torah with the philosophy of Plato. Philo was first great Jewish philosopher and, although, he is a harbinger of Saadya and Maimonides, his writings—in Greek--were embraced by a Church that skewed Philo by focusing solely on his use of allegory. Philo never meant for Jews to abandon the Torah and ritual, he merely took the ideas of the day and recalibrated them for Judaism.

Another great Hellenized Jew writing in Greek was Josephus. He composed his important works in Rome but had strong connections to the Jewish community in Alexandria. His origins were in Judea and his surrender to Rome while leading the first great revolt in the Galilee was not simply the act of a turncoat. In his Jewish War, Josephus described the

66-70 revolt against Rome using the tools of Greek historiography, taking that insurrection seriously though he often is an apologist for the Roman overlords. In his later work Jewish Antiquities, Josephus makes Judaism and Jews the heirs of a great civilization and attempts to explain the Jews to pagans by painting a portrait of Judaism as a philosophy. Finally, he penned polemics against enemies of the Jews. Apion, a scholar of Homer, was a Greek in Alexandria who accused the Jews of ritual sacrifice and argued that the ancient Israelites were ejected from Egypt because they were lepers. These libels that were believed by pagans were challenged by Josephus who, although he abandoned the fight against Rome and had as patrons the Flavian emperors, still was proud of his Jewish identity and Jewish heritage. Not exactly a Hellenized traitor.

Yet, the greatest proof that the Hellenized Jews of the Mediterranean and the Middle East were loyal Jews was the rebellion against Rome staged by the Jews against the Empreror Trajan in 115-117 CE.. Little is known of this revolt. There was no Josephus to record the conflict. And there were no letters like those discovered by Israeli military hero, statesman and archaeologist Yigael Yadin that shed light on the Bar Kokhba Rebellion sixty years after the first failed revolt. There is a paucity of sources on the Jewish revolt against Trajan and this fight against Rome is overshadowed by the earlier and later revolts in the Land of Israel. While this conflict began in Babylonia with Jews participating in rebellion against Rome’s ambitions in the east, revolt spread to Jews living in the Greek-speaking world, including Alexandria. Tensions between Greek and Jew in the Egyptian port city exploded into war and the Roman overlords punished the Jews. The Great Synagogue of Alexandria was destroyed by the Romans and thousands of Jews were killed in the conflict. Jewish memory recounts the devastation of the destruction of the Jews of Alexandria by describing a Mediterranean that turned red with the blood of the Jewish victims. It was a bitter battle that ended the glory and vitality of Jewish life in Alexandria. While Jews lived in the city under the Muslims until modern times, the Romans made sure that Jewish life would never thrive in the port city again.

Most Hellenized Jews were not turncoats and traitors. They were loyal sons and daughters of Israel. We confuse the assimilation that plagues the Diaspora today in the modern epoch with the acculturation that proved a source of strength for many Jewish communities in the ancient and medieval world. Hellenized Jews had a strong sense of Jewish identity and maintained a close connection to Eretz Yisrael. They should provide a lesson for Jewries in the Diaspora today and serve as role models of honor and creativity that will inspire Jews throughout the world.

Below is Eli’s second essay which is only available to paid subscribers. In this week until Chanukah there is a 60% discount on annual paid subscriptions (NOW ONLY £25 / $31). DON’T MISS OUT!

“Chanukah: The Maccabees in the Zionist Imagination” by Eli Kavon

There was little upon which Theodor Herzl and Ahad Ha’am ever agreed. Herzl, the founder of Political Zionism, advocated the establishment of an independent Jewish State backed by the major Western powers. Ahad Ha’am—the pen name of Hebrew essayist Asher Zvi Ginzberg—envisioned a Jewish homeland that would serve as a cultural center for world Jewry and would be a harbinger of a Jewish spiritual renaissance. Ahad Ha’am devoted his life to criticizing the Zionist political establishment and, more specifically, Herzl’s attempts to build up a Jewish State in Israel by currying the favor of the Sultan and the Kaiser. In contrast, Herzl, an assimilated Jew whose base of operation was cosmopolitan Vienna, viewed the Hebrew writer as naïve, an Eastern European Jew who did not understand the fundamentals of realpolitik.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Guerre and Shalom to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.